We study how animals have evolved to defend against bacterial pathogens, and how bacteria adapt to survive within host environments

EVOLUTION OF ANTIMICROBIAL DEFENSES

Infectious microbes are a potent force of natural selection, driving repeated adaptation of host populations. Our lab studies how animal genes, particularly in mammals, have evolved to promote defense against pathogenic bacteria. Bacterial infections are a leading source of human morbidity and mortality around the world, even as resistance to antibiotics continues to spread. Identifying new strategies to treat and prevent bacterial infections is therefore a pressing global health imperative. We apply genetic and genomic approaches to identify patterns of rapid evolution in host defense genes, which guide molecular and cellular experiments to test the functional consequences of host genetic variation.

Our work on host defenses has focused on two major classes of proteins: secreted antimicrobial proteins and cell surface receptors. These studies have revealed mechanisms by which new host defense functions arise, as well as how natural selection can serve to enhance or modify pathogen recognition (Baker et al. 2022; Kohler et al. 2020). We are continuing to investigate the origin and diversification of host defense genes in order to advance foundational knowledge of protein evolution and immune system function.

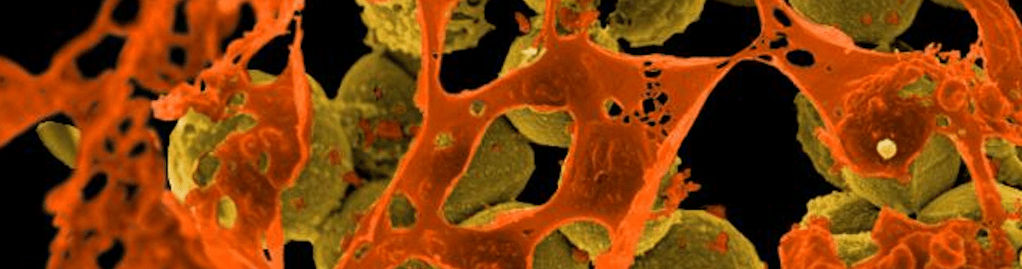

BACTERIAL ADAPTATION TO HOST ENVIRONMENTS

Bacteria are faced with a variety of challenges during colonization or infection including nutrient limitation, predatory viruses (phages), competing resident microbes, antibiotics, and host defense molecules. A major goal of our group is to determine how pathogenic bacteria evolve to overcome these diverse obstacles within the host. We apply laboratory experimental evolution to track bacterial adaptation in real time, integrating molecular and genetic approaches to test the impact of mutations on pathogenic traits. Our work in this area has focused on the major bacterial pathogen Staphylococcus aureus. This bacterium colonizes a large proportion of the human population asymptomatically, but is also a leading cause of skin and soft tissue abscesses, pneumonia, sepsis, and other deadly infections. S. aureus is notorious for its frequent resistance to antibiotics, particularly methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains which are among the most common causes of antibiotic-resistant infections globally. We are investigating how S. aureus adapts to distinct challenges encountered in the host environment, including competing microbes, host defense factors, and phage predation, as well as how bacterial evolution impacts virulence traits and antibiotic susceptibility (Kowalski et al. 2025; Campbell et al. 2025). Unraveling determinants of adaptation in human pathogens like S. aureus could ultimately reveal new avenues for infectious disease treatment and prevention.